How to navigate by moonlight correctly recognizing various lights and perform safe night landings

However, some lights are of fundamental importance. Navigation lights, naturally, to understand the direction of the boat or ship we encounter, and those indicating dangers or cardinal signals.

For these lights, it’s worth doing constant review and imprinting them in your mind, so as to have absolutely no doubt, if for example we see a red light in movement, that it’s a vessel showing us its port side. The problem, especially when dealing with ships and fishing vessels, is that despite having a clear understanding of the different light combinations, sometimes it’s really difficult to identify even the basic ones, namely red and green.

The former are traveling illuminations, with multicolored lights scattered across the entire surface, the latter often have very strong work lights and white searchlights. In any case, especially with some experience and practice, you can understand through the navigation lights which side the boat we’re encountering is showing and, thanks to its movement, in which direction it’s heading. Something different, and somewhat more complex, is landing or navigating at night toward ports or entrances located in areas with restricted waters such as archipelagos.

Thanks to modern electronics, having the exact position and following a course at night is much simpler, but aside from failures of GPS and radar, it’s still the beacons that allow us to navigate along the coast and perform night landings safely.

Each of these lights has its own name and surname in the form of numbers and letters that indicate its characteristics. This data, reported in the list of lighthouses and beacons and on nautical charts, allows us to know which light it is and where it’s positioned on the coast. Near the coast there are other lights, those that indicate dangers. Some are isolated danger signals, others are cardinal danger signals, which tell us which side to pass relative to the signal itself.

In all cases, when approaching the coast at night, you must study the chart in advance, the position of lighthouses and beacons, and based on this information establish an approach course. Once you’ve approached, you must land, that is, you must enter a port or anchor in an anchorage. This is what is meant by night landings.

Doing so by following a night alignment is the technique that allows us to “thread our way” into even complex situations without problems. An alignment, in this case nocturnal but the principle also applies to daytime ones, occurs when two objects on the coast placed at different heights appear to us aligned along the same direction.

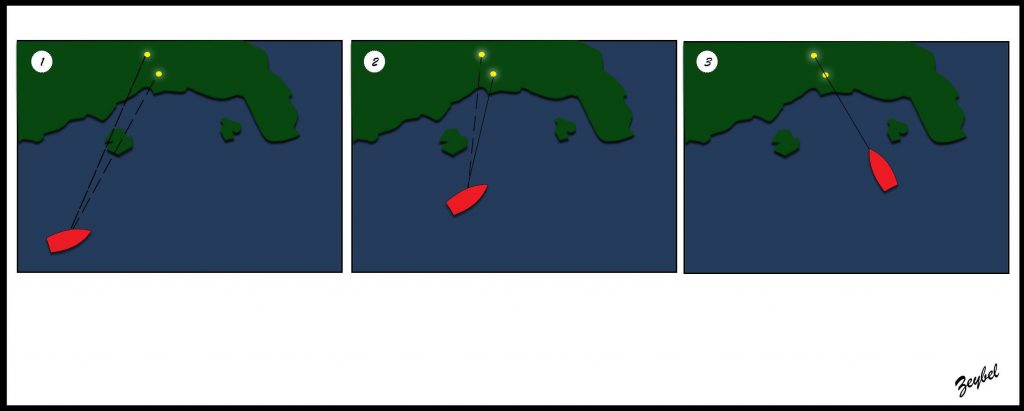

In the drawing above we have represented the sequence of an alignment of two beacons.

In drawing 1 the skipper has identified the two beacons, whose period he knows from the nautical chart, placed on the mountain at two different heights. He naturally sees them offset: the higher one will appear more set back.

Continuing along the course indicated by the procedure reported in the pilot book, the angular distance of the two beacons reduces. (Drawing 2).

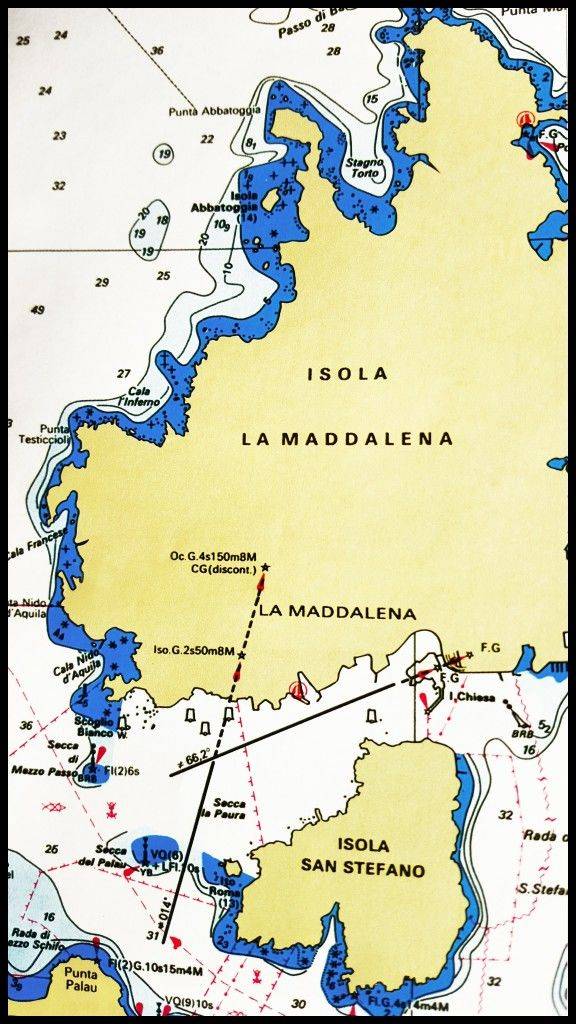

A few moments before finally seeing the two beacons aligned, the skipper alters course (Drawing 3) to take the course indicated by the procedure, keeping the two beacons aligned and thus proceeding safely clear of the rocks. To give a concrete example, let’s take the case of Cala Gavetta, the small port on the island of La Maddalena, if only because our entire editorial team navigates for work and instruction often in those waters.

In the pilot book we can read that coming from “west with easterly course we must alter course to 014 degrees following the alignment of the two green beacons placed on the mountain…”. The beacons have, as mentioned, their characteristics reported on the chart including their period. The captain therefore knows that he must fix his attention on the easterly course to follow and on spotting the two beacons on the island of La Maddalena. Once identified, he continues his course until a few moments before seeing them aligned. At that moment he alters course to 014 degrees.

Attention, all bearings and courses plotted on the chart are true. Therefore, theoretically, they should be corrected to transform the true bearing into a compass heading to give to the helmsman. The difference in reality is so small as to not even be readable on the compass.

Having altered course to 14 degrees, we continue keeping the two beacons aligned until – as the pilot book tells us – we intercept a new alignment on our starboard of two green flashing beacons to follow for 66.2 degrees. Once the new alignment is taken, it will be followed until, on our port side, we see the green beacon and the red one at the entrance to the port of Cala Gavetta. At night, paying maximum attention to ferry traffic between Palau and Maddalena, we have thus managed to land perfectly navigating in the dark in waters full of rocks and shallow waters.

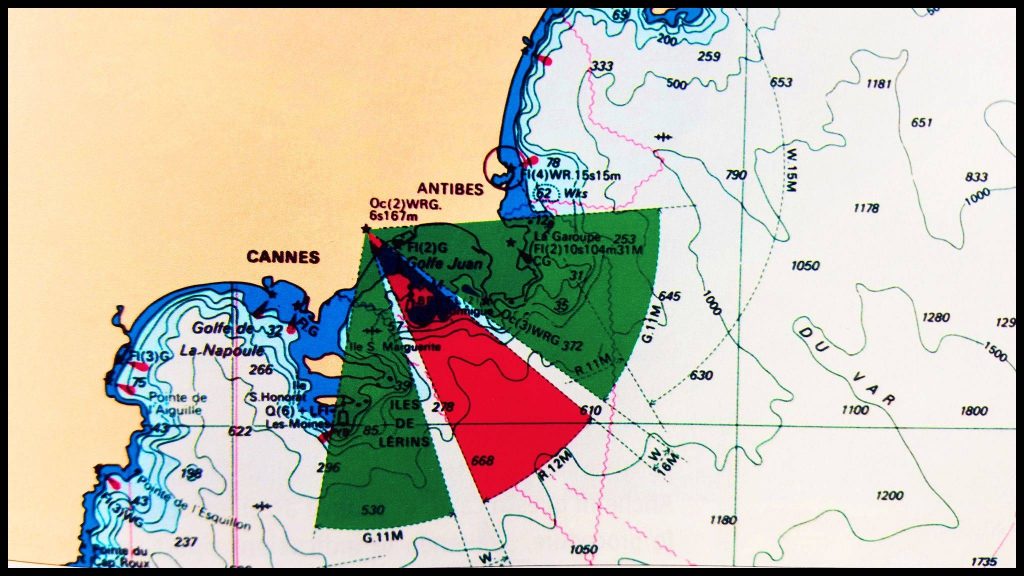

These are light beams divided into sectors of different colors. In addition to representing true corridors for landing, thanks to the procedures reported in pilot books, they allow following safe courses to round headlands, navigate in fjords, tackle narrow passages between rocks and shallow waters.

In the case of these lights, the green light does not indicate all clear. It usually indicates, as in the drawing reproduced above, a limit just like the red light. In the drawing we indeed see the approach course to the coast indicated by the sector light northeast of Cannes. We see a green sector on the left, a much smaller white one, another red sector, a second white one and finally the last green one. The white sectors are the possible landing corridors.

But if continuing our navigation along the coast, we enter the green sector, that is, we see the green light, we know with equal certainty that we cannot alter course toward land until we encounter the white light of the same lighthouse again. At that point we can alter course toward land safely.

In conclusion, we propose a principle that in our opinion is fundamental for the safety of night landings. If navigating at night you are not certain of your position and the landing course to follow, never tempt fate based on your memories of daytime navigation in the same area. When in doubt, stay outside and wait for the dawn light to land. And are you ready to land at Marina Porto Antico?