Nautical Terms and Dialectal Inflections: A Story Passed Down Through the Centuries

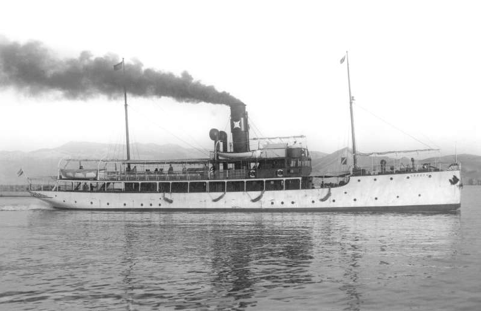

Indeed, it must be considered that the “strength” of the Austro-Hungarian navy was made up of officers and sailors predominantly originating from the Adriatic coast who, during the long Venetian domination, came from all the lands once occupied by the Serenissima, starting from the Venetian lagoons and reaching the farthest borders of Dalmatia.

History, therefore, tells us that Italian literary nautical terms were mixed with the dialect, or rather with the dialects spoken by the seafarers of the “old provinces” and, absorbed by daily practice, they then became the official jargon of the Austrian war navy.

This work was then followed by a supplement in which new words formed with the technological development of that era were collected and added by a certain J. Heinz, and therefore could not be included in Dabovich’s work.

From the combination of these official and literary sources, and with the help of the oral tradition of some seafarers, the “Collection of Seafaring Terms from the Dialect of Our Provinces” was born, which is the official title of the work curated by Giacomo Furlan and which today surprises us with the abstruse remoteness of its terms compared to those used today by seafarers.

The current dictionaries of nautical terms, which are numerous, are rich in foreign neologisms, predominantly of Anglo-Saxon origin, but I can show you that the wanderings of sailors, even then, that is, at the beginning of this century, drew inspiration from other languages, but they dialectalized them and made the nautical terms more familiar, at least in sound.

That the anchor well was called “sliper” is clearly a term borrowed from the English slipper and the verb to slip, which indeed means to slide. Similarly, the casseretto: the small deck that on ships was at the stern higher than the cassero, in the dialect of the old provinces was called pup, clearly derived from the English poop.

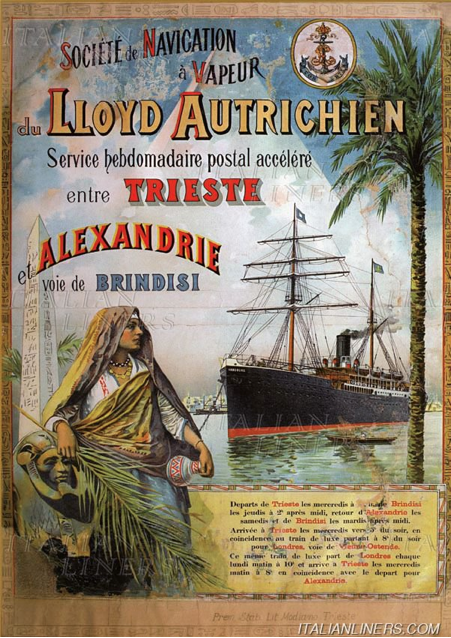

From a neologism taken from the French paquebot, which in turn was taken from the English pack or packet (package or suitcase) and boat, comes “el pacheto”, which meant a small boat used to perform a regular service between port and port. The postal steamer that, along the Istrian coast, called at Umago, Cittanova, Parenzo, and down to Pola was therefore a “pacheto.”

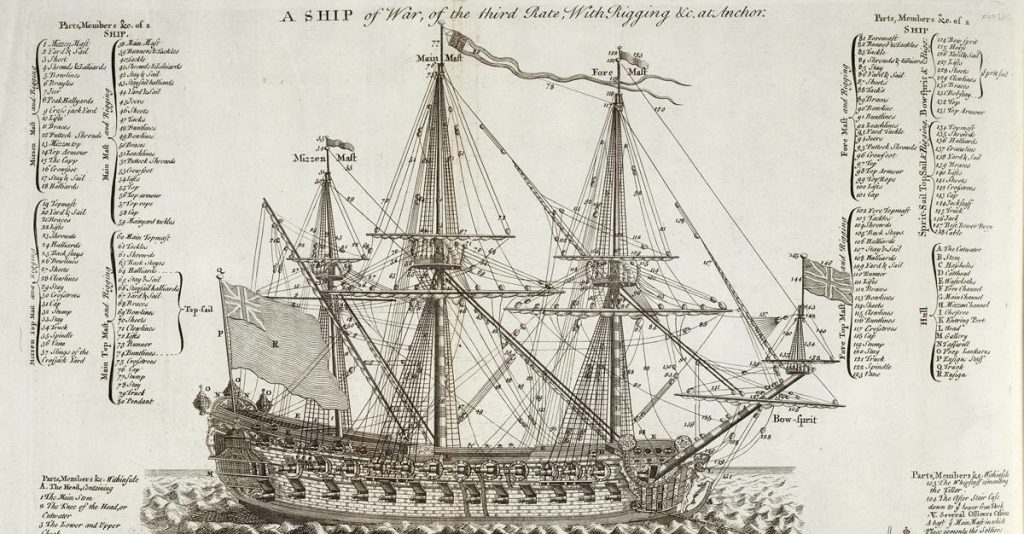

Browsing through the entries listed by Furlan and then the notes added by the historian and philologist Gianni Pinguentini, one encounters unexpected curiosities regarding nautical terms. The snap hook, our common carabiner, was called “papagal”, the bowsprit shrouds were called “mustaci”, the screw jack or the drum of the windlass referred to a sturdy monkey, a figurative synonym for an ugly and foolish man, and therefore was called the “macaco.”

In the constructive architecture of the hull, between frames and ribs, between the floor timber and the keelson, at the extreme end of the boat’s framework, there was also the “putana”: because this was the name of the very last frame or rib at the stern, with an evident reference – explains Pinguentini – to the very last place occupied by the prostitute in the social hierarchy.

Nautical terms harsh, sometimes coarse, but quite often sailors tempered them with sudden devotions, when, alone there in the middle of the sea, they faced difficult moments during navigation and therefore, at the order “tira mola gabia” (tack!) the entire crew responded to the command with the invocation: Saint Luke and Saint Matthew.

And today? It sounds posh if some skippers, when ordering the tack, shout: Lee-o!