The wind is the sailor’s best friend, a companion of many adventures and a source of great emotions. However, when mooring and setting sail, strong gusts can affect the maneuver and quickly cause significant damage. We have already provided some advice on how to moor, now it’s time to share some tricks for those setting sail without a bow thruster installed on their boat.

Obviously, the first factor to consider is the direction. It is essential to understand the wind’s effect on the maneuver, so we can counteract or take advantage of it. Let’s try to analyze three different typical situations.

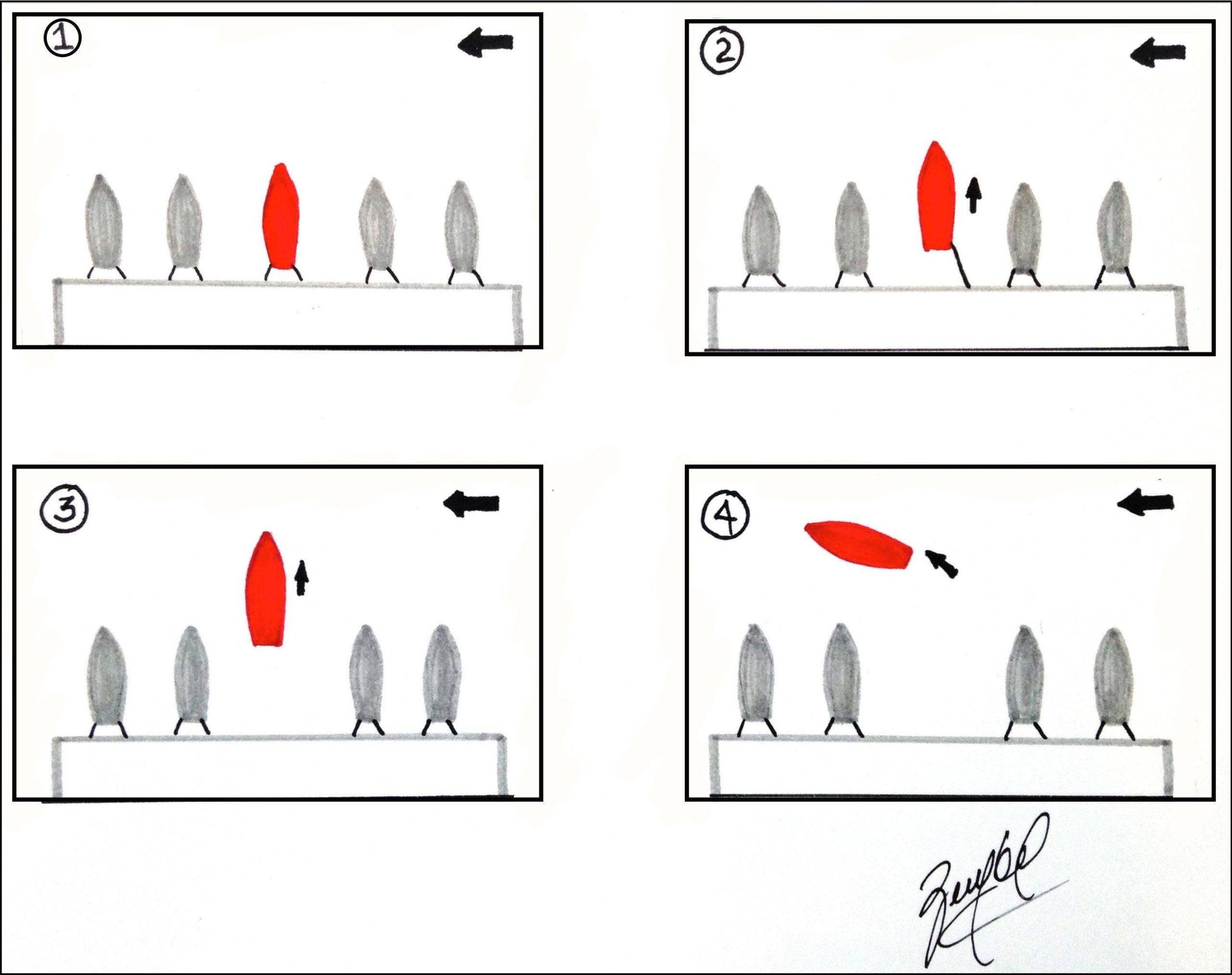

With a light crosswind, but strong enough to slowly push the bow down, it is useful to use the crew, if present. In this case, the person at the bow can pull on the dead body line, guiding the boat’s exit, and then release it once sure they can dock and exit without difficulty.

If you find yourself alone, you need to release the leeward lines, so you remain moored with the stern line and the windward dead body. At this point, you need a longer mooring line, letting the stern line run. A forward gear will tension the windward stern line, preventing the bow from falling leeward. Once the dead body is released, quickly return to the cockpit to release the stern line. Now you can exit, adjusting the engine power.

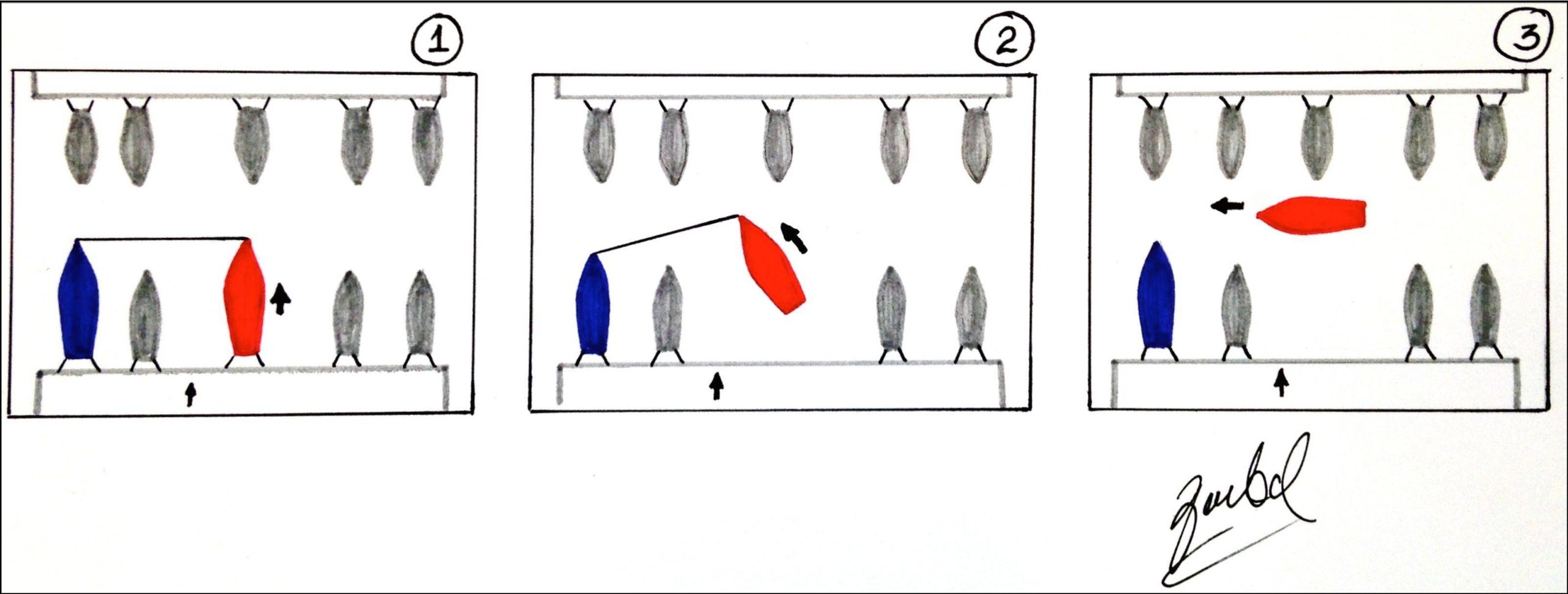

The second typical situation we analyze is the boat moored in a channel with two opposing rows of boats. With a fresh tailwind, as soon as the bow is turned to the right or left, the wind itself will push laterally towards the bows of the boats in front.

In this case, the solution is more challenging, and if we want, creative. The best move is to pass a double line between the bow of the departing boat and the bow cleat of another boat, moored in the direction of the intended course. Now you can release the dead body and then the stern lines, asking a crew member to adjust the tension on the double line to support the windward bow while slowly exiting the mooring.

The maneuver also works with a fresh crosswind at the mooring: the only difference is that the bow is supported with a line passed on the cleat of a windward boat.

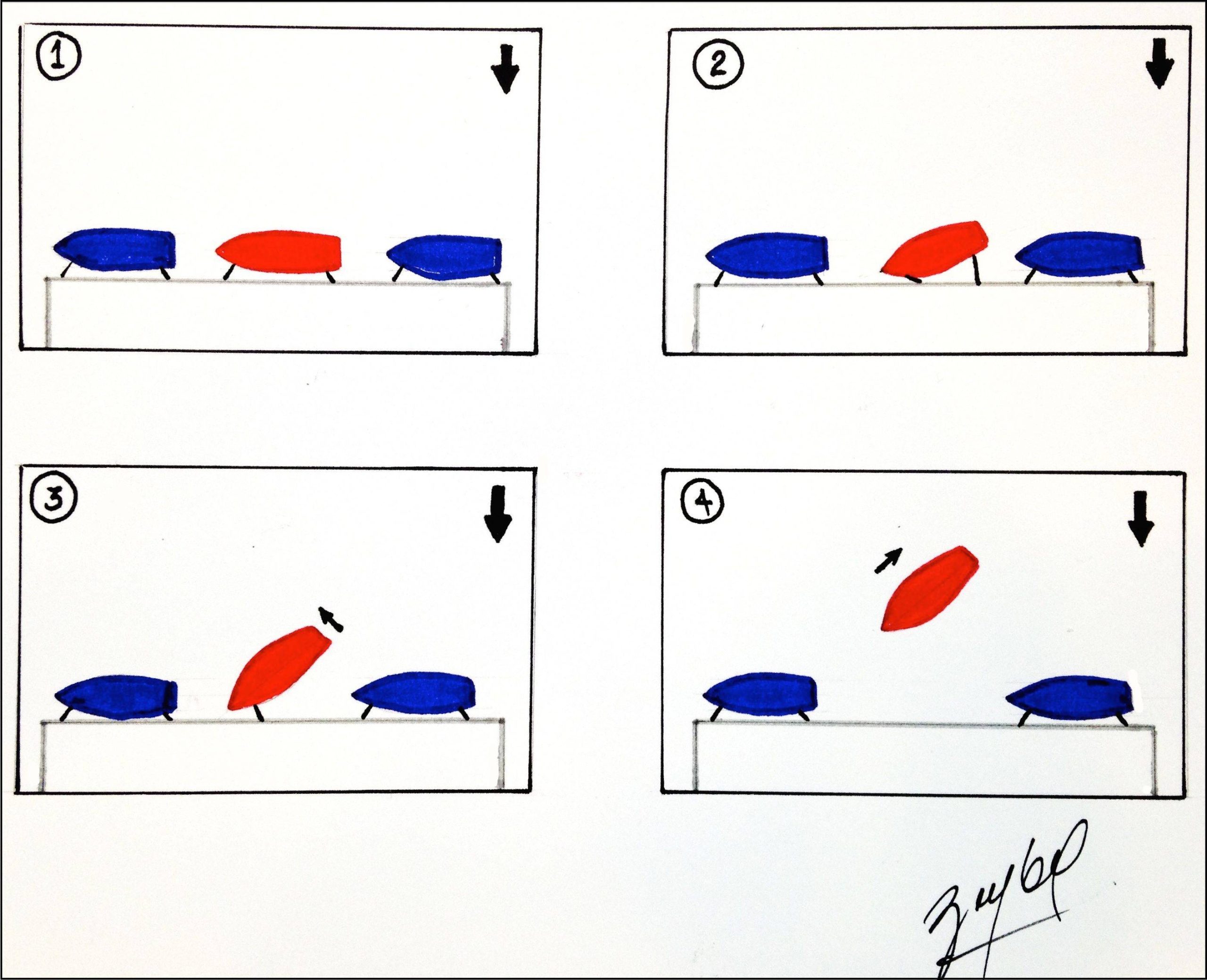

Finally, the last situation we consider is one of the most difficult to face: the one with the wind pressing the boat against the dock, moored English-style and with little maneuvering space due to the presence of other boats. The scheme is quite typical, as it is common when docking to refuel.

In such a circumstance, it is necessary to exploit the power of the spring, positioned at the bow of the most advanced cleat to a dock bollard, identified towards the stern. After freeing from all other moorings, you need to engage forward gear, instructing a crew member on how to protect the bow, lowering a fender at the contact point between the bow and the dock. If the maneuver is performed correctly, the spring will bring the bow closer to the dock, rotating the stern outward. Once the possibility of moving freely is confirmed, you need to put the gear in neutral and then a sharp reverse gear to release the bow spring.

In conclusion, we remind you of one last always useful piece of advice: if you don’t feel comfortable casting off in those weather conditions, don’t do it. No one forces you, and it’s foolish to take unnecessary risks.